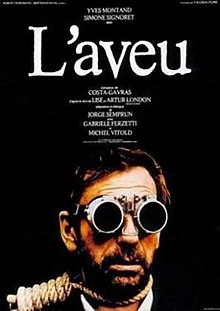

Directed by Costa-Gavras

The methodical pacing of the film allows the viewer to experience the Kafkaesque nature of the captivity Ludvik must endure. At the start he begins to realize he's being followed, and is eventually taken into custody. Meanwhile Ludvik's wife Lise (Signoret) is forced to leave her job as a radio broadcaster and to work in a factory.

Gavras directs the film mostly from Artur's point of view. When first brought in his clothes are taken away and he's stripped of his identity. He's put through sleep deprivation as he goes through hours of interrogation with various bureaucrats. They employ a "good cop, bad cop" routine with some officials constantly screaming threats (there's a mock execution at one point) to a fatherly interrogator offering food and reassurance.

Historians agree (it was obvious at the time) the sudden crackdown on Czech officials was driven by antisemitism. Ludvik's put through endless questioning about his time with the French Resistance and supposed contacts with American intelligence. Clearly innocent, he's coerced into signing several confessions, while being told he'll never see his family again. Eventually Ludvik faces trial with the other defendants in a darkly comic staged event made for the cameras. Ludvik received a life sentence, most of the defendants were executed, and eventually due to changing political tides after Stalin's death in 1953, he was freed.

Few films have placed the audience into the totalitarian mindset so effectively. It's like a bizarre equation. Loyalty to the state and ideology appears to reign above all else, but it's slippery. Such systems allow sociopaths to flourish and lead otherwise decent people into debased acts. It's something like a cult, but Stalinist regimes were more complicated, to survive one almost needs to hold two opposing thoughts at the same time, basically Orwell's doublethink. To go against ideology is unthinkable and may spell total loss of freedom or worse, yet survival and promotion may entail going against the rules.

The Confession posits basic questions on the individual's relationship to the state, the use of torture, and ultimately human rights. Article 5 of United Nations Declaration of Human Rights prohibits torture yet states continue to use it, always in the name of national security. Totalitarianism, today the term illiberal is often used as a stand in, is based on dehumanization and The Confession illustrates the abnormal psychology of such a system.

No comments:

Post a Comment